What is 5-Axis Machining?

Milling is one of the old but ever young manufacturing processes. According to chroniclers, the first milling machine for metal materials was developed in the early 1800s. The next important evolutionary step can then be dated to around the middle of the 19th century, when a universal milling machine was introduced by the Brown & Sharp company. For more than a century, three dimensions were then used in conventional milling, named X-axis, Y-axis and Z-axis following the Cartesian coordinate system. The X-axis is (generally) horizontal. The Y-axis moves in the eye of the beholder from front to back and vice versa. And on the Z-axis the upward and downward movements run.

For more than a century, therefore, the three linear traversing axes defined the geometric limits of the conventional milling process. Although it later became possible to position the spindle at a desired angle or to clamp workpieces with a rotating fixture, shaping machining always remained stuck in the 3-axis mode. Nevertheless, milling developed into one of the dominant manufacturing processes in industrial metalworking.

Although the development of NC and later CNC control since the 1960s has increasingly expanded the possibilities of machining, 3-axis milling is still indispensable today. This is exemplified by a joint study conducted by the Fraunhofer Institute for Production Technology IPT and the WBA Aachener Werkzeugbau Akademie in 2018, according to which 3-axis milling is still the dominant axis configuration even in toolmaking, accounting for almost 50 percent, whereas only about ten percent of 5-axis configurations were used four years ago.

The reasons given in the study for the surprisingly low prevalence of 5-axis milling are obvious. For one thing, a large number of the workpieces produced do not necessarily require simultaneous 5-axis machining. On the other hand, the low prevalence of 5-axis machining can be explained by greater challenges for the user companies, especially in programming. But it is precisely in these two aspects that the interaction of innovation and evolution is now playing into the hands of 5-axis milling.

5-axis milling with a future

First of all, when milling with 5 axes, it is important to distinguish whether the tool can be merely positioned in space with two additional rotary axes in addition to the three linear axes, or whether it can be moved fully simultaneously. In the first case, we are talking about 3+2 axis machining, in which the fourth and fifth rotary axes hold the workpiece in a fixed orientation, but the milling itself is again performed in 3 axes. In "real", i.e. simultaneous 5-axis milling, on the other hand, all 5-axes of the machine can move interpolating to each other in any constellation.

5-axis simultaneous milling on the advance

It should be noted at the outset: The market penetration, which is still quite low from a 5-axis perspective, is likely to shift substantially in favor of 5-axis milling in the future, despite the challenges of its use. This was also shown (by way of example) in the previously cited study four years ago. At that time, the toolmakers surveyed assumed a future growth in 5-axis processes (in finishing) of more than 50 percent.

Obviously, the advantages of 3D milling are becoming more and more calculable and lucrative for users. In terms of production technology, for example, thanks to the five numerically controlled axes, the position of the tool and its cutting edges can be positioned at any point on the workpiece at any time, traversing along a curved surface (free-form surface) while maintaining any desired angle to the workpiece surface with high precision.

One of the greatest advantages of a 5-axis machine is the ability to produce complex workpieces and precise components in mostly just one setup, with less time and lower costs. As a result of this degree of freedom, 5-axis simultaneous machining can be used to produce virtually any workpiece contour in a single operation without reclamping. This saves unproductive idle time and also avoids inaccuracies when changing from one machine to the next. In addition, the tool can always be perfectly positioned relative to the workpiece. This ensures that tools in shorter standard lengths can be used. This in turn increases rigidity, enables higher feed rates and extends tool life.

The market-side reasons for the growing share of 5-axis milling are the trend towards more demanding and complex workpieces in ever smaller batch sizes. Added to this are the increasing demands on the precision and surface quality of the components as well as ever shorter response times and delivery periods. In addition, manufacturers such as DMG MORI are also pushing for greater acceptance of adequate 5-axis machining centers. In addition, machine tool manufacturers can rely on increasingly intelligent controls, which in the medium term will even bring the workshop programming of 5-axis machining tasks into the user's field of vision. And finally, suppliers are also continuing to upgrade the digital process chain from CAD to CAM to CNC. Therefore, many experts assume that fully automatic NC programming including intelligent simulation routines could soon be possible.

Machines for 5-axis simultaneous milling

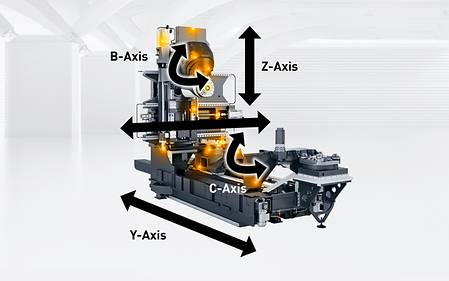

However, the basis of success is and remains, of course, the adequate milling machine or the right machining center. In addition to the X, Y and Z axes, the A, B and C axes take over the necessary rotary movements of the spindle or the workpiece or the clamping table in various constellations, depending on the kinematics of the machines. In fact, the universal relative movement between the tool and the workpiece can in principle be achieved in three ways, as the legendary CNC manual has taught us:

- with fixed workpiece and two swivel axes of the tool,

- with a stationary tool axis and two swivel movements of the workpiece, e.g. by means of a swiveling rotary table, or

- with one swiveling movement of the tool axis and one swiveling movement of the workpiece, which are offset from each other by 90°.

In swivel table milling machines, for example, the table with the A axis rotates around the longitudinal travel path of the X axis, while in milling machines with a swivel head, the B axis of the milling head rotates around the Y axis and at the same time the C axis rotates around the Z axis. Which constellation is the right one for a user is always decided by the customer's workpiece spectrum.

Final remark

In conclusion, it remains to mention that the fundamentals of 5-axis milling on milling machines are no different from 5-axis milling on lathes. Here, questions then rather arise about the advantages of process integration. That, however, is a completely different "story", which we will clarify in a later article.